Women in the First World War

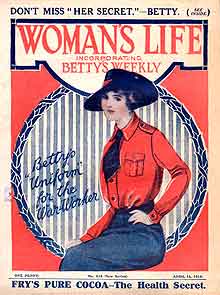

Women played a massive part in the war effort during the First World War – and their taking over the roles of so many men was widely reflected in the magazines of the day. The changes affected all aspects of their lives, from fashion – as in this Woman's Life cover showing 'Betty's uniform for the war-worker' – to potential mortal perils. The ‘war to end all wars’ started in August 1914 and within weeks Lord Kitchener’s volunteer recruitment campaign took 300,000 men off the streets and away from jobs on the land and in industry. By Christmas, the total was a million, and almost 2.5 million men volunteered before conscription was introduced in 1916. Ultimately, 5.7 million men from the British Isles served in the First World War (compared with 3.8 million in World War II). Approaching 900,000 were killed – one in 20 of the male population – and almost twice as many injured.

Women played a massive part in the war effort during the First World War – and their taking over the roles of so many men was widely reflected in the magazines of the day. The changes affected all aspects of their lives, from fashion – as in this Woman's Life cover showing 'Betty's uniform for the war-worker' – to potential mortal perils. The ‘war to end all wars’ started in August 1914 and within weeks Lord Kitchener’s volunteer recruitment campaign took 300,000 men off the streets and away from jobs on the land and in industry. By Christmas, the total was a million, and almost 2.5 million men volunteered before conscription was introduced in 1916. Ultimately, 5.7 million men from the British Isles served in the First World War (compared with 3.8 million in World War II). Approaching 900,000 were killed – one in 20 of the male population – and almost twice as many injured.

The campaign of advertising and posters to motivate volunteers was abetted by the attitude of the mainstream magazines and newspapers and magazines. So, although women could not fight in the British army, they took on jobs during the Great War that they had rarely had access to before. By mid-1916, it was estimated that 766,000 women had replaced men in civil employment alone, and many more had taken up work in munitions factories and other occupations that the war had generated, with their voluminous initials such as WAACs, VADs, WRNSs and WRAFs.

The changes were all grist to the mill for cartoonists in magazines such as Punch, Tatler, Bystander and London Opinion.

- Khaki for men, dress-down fashion for women

- Suffragettes and votes for women

- Reactions to women in men's jobs

- Heroines at war

- The thrill of a woman in uniform

- Women on the land

- Changed attitudes towards women

- Quoting Magforum in your work

Khaki for men, dress-down fashion for women

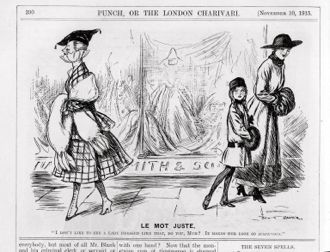

City streets were soon filled with men in khaki and there was pressure on women to moderate their clothes to express solidarity with the troops.The Punch cartoon above (10 November 1915, p390) was by one of the magazine's most popular and long-serving contributors, Lewis Baumer. In it, the girl tells her mother she is 'suspicious' of the flashy dresser (also a reference to the spy scares that were common at the start of the war). The caption for 'Le Mot Just' reads: ‘I don’t like to see a lady dressed like that, do you, Mum? It makes her look so suspicious.’

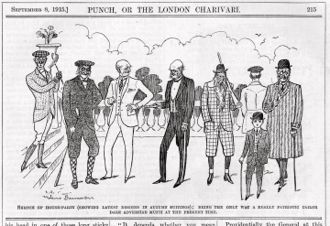

For 50 years, Paris had set the fashions for women while London had dominated style for men. Yet, once war began, men of service age who were seen not in uniform were viewed as pariahs. Below, Lewis Baumer jests that the latest men's fashions can only be modelled by aged men and boys (Punch, 8 September 1915, p215).

Suffragettes and votes for women

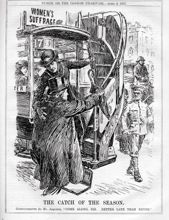

This Punch cartoon was the 'Big Cut' – the whole-page political cartoon summing up the event of the week – for the issue of 4 April 1917 (p224). The 'Catch of the Season' shows Asquith being helped up on to the women’s suffrage omnibus. The conductorette is saying to the prime minister: 'Come along, sir. Better late than never.' In June 1917, with Asquith's belated support, the House of Commons passed the Representation of People Act, which became law the following year and gave voting rights to many women. After this, all men over 21 could now vote. Women who got the vote had to be over 30, or over 21 and the owner of a house or married to a householder. Giving all women the same rights as men would have meant men being outnumbered because of war casualties, which was clearly a step too far for the government! It wasn't until 1928 that the act was expanded to give all women over the age of 21 the right to vote.

Emmeline Pankhurst had been waging her fight for equal rights for twenty-five years. She founded the Women Social & Political Union with her three daughters in 1903 and the WSPU had its own newspaper, Votes for Women, from 1907. The first editors were Emmeline and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence. By the time war broke out, this was a penny weekly and adopted the strapline 'The War Paper for Women'. Later, the WSPU published the Suffragette, and one cover depicted the Press as part of the 'forces of evil' denouncing the suffrage movement portrayed as 'the bearers of light'. Such was Pankhurst's famed determination that a colour postcard in 1915 showed a saluting officer telling Kitchener:

‘My Lord, it is reported that the Germans are going to disembark at Dover!’

Kitchener, in full uniform with a quill pen in his hand and a map of the empire marked in pink on his desk, replies:

‘Very Well! ’phone Mrs Pankhurst to go there with some suffragettes, and that will do!’

Pankhurst's Votes for Women campaign was called off when war broke out and women were desperately needed in munitions factories. However, the suffragettes did not go away. Kitchener received a suffragist deputation at the War Office in January 1915, for example, demanding that arbitrary restrictions should not be imposed on soldiers’ wives by commanding officers, such as not being served in hotels and public houses after six in the evening. Women from the landed gentry would soon find themselves working alongside working class women.

Reactions to women in men's job

Frank Reynolds sums up the potential embarrassment for some men in being helped by women. Here, the haughty-looking conductorette is helping a hapless male. The caption reads: 'Humiliation for Jones, who hitherto has been accustomed to drop off unaided.' (Punch, 5 April 191, p229)

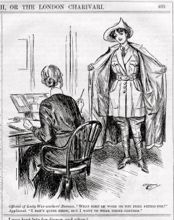

Women being besotted with fashion was the punch line for this cartoonist (Punch, 20 June 1917). The official at the Lady War-workers' Bureau asks what sort of work the girl feels fitted for. The girl replies, displaying a uniform of her own design:

'I don't quite know, but I want to wear these clothes'

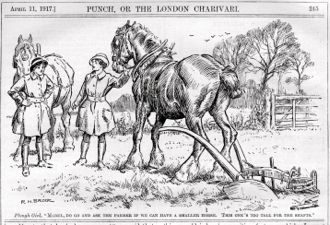

Then again, some women were portrayed as useless. Here, R.H. Brock (Punch 11 April 1917, p245 ) has one land girl asking the other:

'Mabel, do go and ask the farmer if we can have a smaller horse. This one's too tall for the shafts.'

Heroines at war

Women were not allowed to fight in the armed forces and even those who served as nurses were not allowed at the front. However, both rules were broken by intrepid women.

The execution of 49-year-old British nurse Edith Cavell in October 1915 was a cause célèbre. The incident was portrayed in a London Opinion cartoon. ‘Britons. Avenge!’ was the title with a bugler standing over the prone body of the nurse and sounding a call. The caption ran: ‘The brutal murder of Nurse Cavell by the Germans sent a thrill of horror through the civilised world.’

Cavell was matron of a training school for nurses in Brussels and stayed on after the city fell in the first few weeks of the war. She cared for wounded soldiers irrespective of nationality and was arrested after helping Allied soldiers escape to Holland. Cavell admitted to the charges and was sentenced to death. Diplomatic efforts to persuade the authorities to commute the sentence were rejected and she was executed by firing squad. As well as journalists running the story, a propaganda campaign publicised the incident and the Essex recruitment committee produced a poster of a photograph of Cavell with the text: ‘Murdered by the Huns. Enlist in the 99th and help stop such atrocities.’ Cavell herself was reported as saying as she awaited her fate: ‘Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness for anyone.’ She was hailed as a heroine and martyr with a statue just off Trafalgar Square and the Cavell Nurses’ Trust that helps nurses in time of need was set up in her name in 1917.

Elsie Knocker and Mairi Chisholm were two of the most famous people during the war. In 1914, the 29-year-old divorcee and her 18-year-old friend volunteered for the Flying Ambulance Corps. Once in Flanders, they set up their own, unofficial, first-aid station in the cellar of a collapsed house near the Belgian front line in the village of Pervyse (Pervijze). Their action was against British regulations, but they carried on regardless, were lauded by the press and dubbed the ‘heroines of Pervyse’.

Elsie Knocker and Mairi Chisholm were two of the most famous people during the war. In 1914, the 29-year-old divorcee and her 18-year-old friend volunteered for the Flying Ambulance Corps. Once in Flanders, they set up their own, unofficial, first-aid station in the cellar of a collapsed house near the Belgian front line in the village of Pervyse (Pervijze). Their action was against British regulations, but they carried on regardless, were lauded by the press and dubbed the ‘heroines of Pervyse’.

In 1915, Knocker and Chisholm were decorated twice by the Belgians. They were credited with saving thousands of lives and, as the only women working on the Western Front, they were 'les madones de Pervyse' to the troops (the ‘madonnas’ nickname came from a shrine over the entrance to their dug-out). They toured Britain to raise funds for supplies and an ambulance. Knocker married a Belgian airman whose plane was brought down in no man’s land near their post, becoming Baroness T’Serclaes. This cover of Home Chat, the best-selling women’s weekly, shows them with their Military Medals from the British authorities (11 April 1918). However, they were both injured in a German gas attack in 1918 and they ultimately had to abandon the post. Back in Britain, they joined the newly formed Women's Royal Air Force. After the war, the Baroness T’Serclaes promoted the forming of a company to employ demobilised troops as actors. She wrote about the idea of a 'film colony of warriors', the United Services Film Colony, in The Shadow Stage, a cinema magazine.

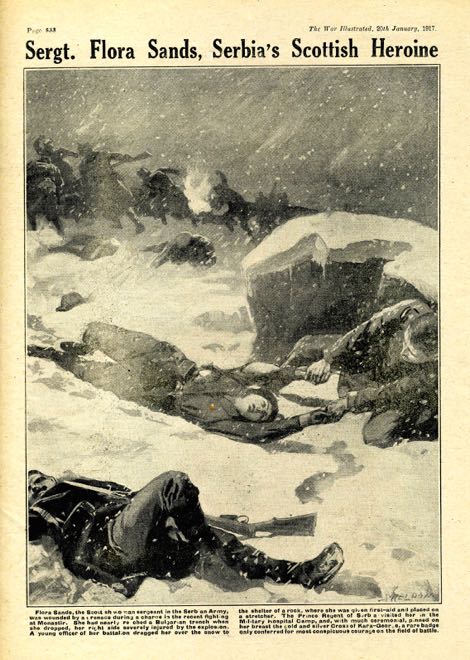

The tragedy of their relationship was that Knocker had lied about her husband being dead, when in fact she was divorced; when Chisholm found out, she renounced their friendship, such was the stigma of divorce at the time. Knocker served as an officer in the Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) in World War II. Flora Sandes was the only British woman to fight as a soldier in WWI. She volunteered for a Red Cross nursing unit and then moved to an ambulance team attached to a regiment of the Serbian army. From there, she fought with the regiment. She was wounded at the battle of Monastir in 1916, one newspaper reporting that she was the only woman in a field hospital with 1,600 beds. The Prince Regent of Serbia awarded her the gold and silver cross of 'Kara George'. She was promoted to sergeant and came back to Britain the following year to raise funds. She returned to Serbia and was wounded again in 1917 but returned to action. Sandes was finally demobilised in 1922. She was called up for service again in 1941 but was interned by the Germans and then returned to England. Sandes died in Ipswich in 1956.

Flora Sandes was the only British woman to fight as a soldier in WWI. She volunteered for a Red Cross nursing unit and then moved to an ambulance team attached to a regiment of the Serbian army. From there, she fought with the regiment. She was wounded at the battle of Monastir in 1916, one newspaper reporting that she was the only woman in a field hospital with 1,600 beds. The Prince Regent of Serbia awarded her the gold and silver cross of 'Kara George'. She was promoted to sergeant and came back to Britain the following year to raise funds. She returned to Serbia and was wounded again in 1917 but returned to action. Sandes was finally demobilised in 1922. She was called up for service again in 1941 but was interned by the Germans and then returned to England. Sandes died in Ipswich in 1956.

This illustration, signed 'Sheldon', of the wounded Sandes being dragged from the battlefield is from War Illustrated (20 January 1917).

The thrill of a woman in uniform

There was a certain thrill to the sight of women in everyday men’s jobs, as Times journalist Michael MacDonagh later recalled in his published diaries:

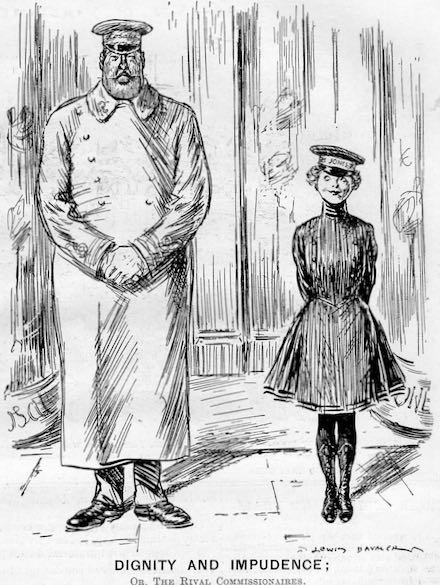

‘On seeing his first policewoman in her ‘dowdy uniform, sex keeps breaking through in bright eyes, shapely ankles and ripe red lips ... a susceptible lad might well be tempted to commit an offence for the delight of being led captive – abducted, in fact – by one of these fair damsels ... The hall-porter at some of the big hotels is an Amazon in blue or mauve coat, gold-braided peaked cap and high top-boots – a gorgeous figure that fascinates me. But my favourite is the young “conductorette” on trams and buses, in her smart jacket, short skirt to the knees and leather leggings.’

The 'Dignity and impudence' cartoon above is Lewis Baumer's take on two rival commissionaires (Punch, 24 May 1916, p347).

Women on the land

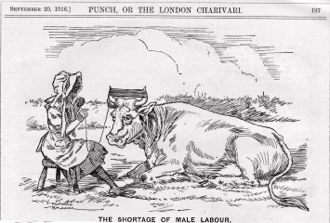

The shortage of male labour prompted Ricardo Brooks to depict a cow girl having to enlist the help one of her herd in winding balls of wool (Punch, 20 September 1916, p197).

Some 260,000 women ultimately formed the Land Army, three times as many women as were working on farms at the war’s start. There was even a magazine, the Landwoman, to promote the movement.

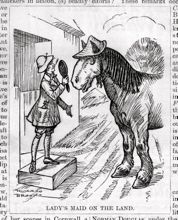

Old habits died hard for Ricardo Brooks, with this lady’s maid spending her time beautifying a farm horse with plaits and sun hat (Punch, 9 August 1916, p116).

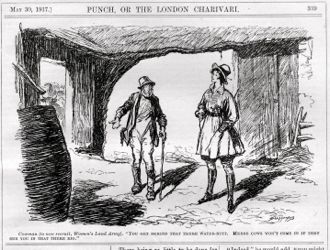

Claude Shepperson makes a reference to the strange clothes that farm girls wore. The cowman is saying to the new recruit Women’s Land Army: ‘You get behind that there water butt. Mebbe cows won’t come if they see you in that there rig’ (Punch, 30 May 1917, p359).

Changed attitudes towards women

Four upper-crust women who could not give up their martial experiences were depicted in 'After the War: The War-Work Habit' (Punch, 1917 almanac). Here, Lady Albert Hall (a former Red Cross ambulance driver) is dealing with her broken-down car in Bond Street. Other women shown are: a former platoon commander in a woman's volunteer corps drilling her gardeners; a former land girl in smock and corduroys arranging flowers for the dining table; and a munitions worker stepping in ahead of a butler to fix a tap.

This is one of four frames from 'The Heroine of the New Novel' by Lewis Baumer (Punch, 2 May 1917, p287). It shows a woman billposter. According to one account, this was one role where women ‘needed courage, especially the first pioneers, to face the male ribaldry to which the public nature of their work inevitable exposed them’ when pasting up bills made up of up to thirty-two sheets – about ten feet by thirteen feet – from a ladder. Baumer's caption reads:

'I'm so fearfully sorry!' said a sweet young voice in distressed accents. And then he became aware of a dainty little foot and ankle coyly protruding from a blue trouser almost at a level with his eye.

The other frames showed instances of man coming into a romantic situation with a land girl, a conductorette and a motorcycle despatch rider.

Quoting Magforum

I'm very happy for people to quote from Magforum pages – but you should acknowledge this by giving the Magforum page address and ideally adding a link to the page. All the material on Magforum is copyright – the site has taken a decade to build up and it's a one-man band, so you can imagine how how much time and effort has gone into it. Income from advertising pays for the site's fees, research costs and buying magazines.

Referencing Magforum will benefit you and your website too, because:

- if you are writing an academic work or a book, you will remove any possibility of either being accused of plagiarism or copyright theft;

- if you work in the magazine industry, it shows you have a strong interest in your work and are building in-depth knowledge that you can apply in doing your job;

- Magforum is heavily used by academics and researchers and you will be referencing a site with a strong reputation.

If you are building a web page, note that you can make a link straight from your page to a section on a Magforum page. For example, to jump to the section above called 'Heroines at war':

- Click on the menu list at the top of this page to take you to the heroines section. Copy the link from the address window in your web browser: http://www.magforum.com/war_and_magazines/

magazines_and_war.html#her - It is the #her part that finds the exact section within the page;

- If you do not know how to make a live link, just paste in the address into your text and your readers can copy and paste this into their web browser.

To cite this page in a dissertation:

- Quinn, A. (2020) 'Magazines at war'. www.magforum.com/war_and_magazines.html (accessed: GIVE THE DATE)